Sailors Shipwrecked in Icy Seas

Dad never told us details about his harrowing World War II experience of being shipwrecked in the frigid waters off Iceland during a violent storm. So I pieced this story together from news clippings, photos, and other evidence that has survived for the nearly 80 years since.

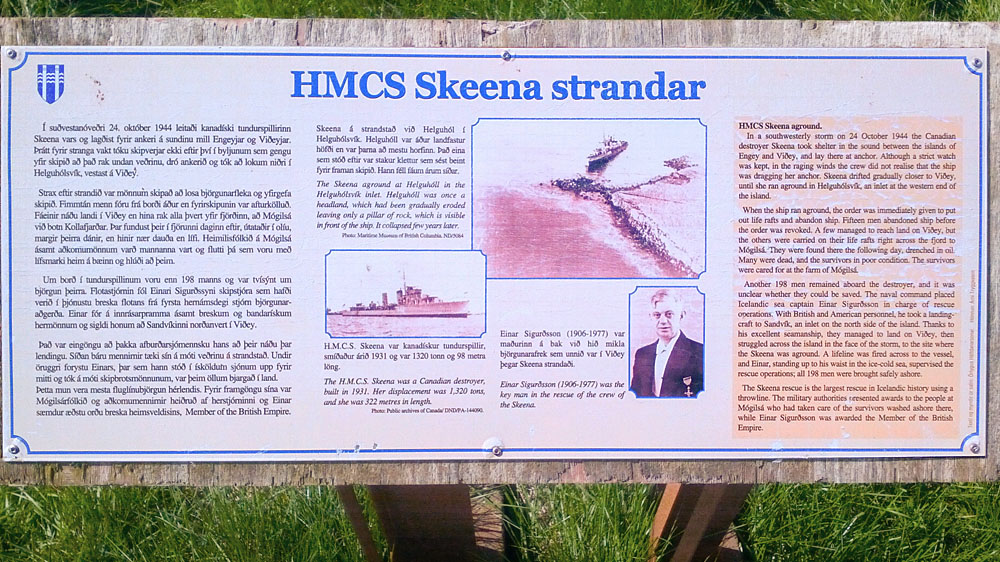

On Tuesday, October 24th, 1944, HMCS destroyer Skeena and four other Royal Canadian Navy ships were ordered to leave their anti-submarine patrol duties south of Iceland and drop anchor between two small islands off Iceland’s southwest coast near Reykjavik. A severe storm was approaching, which at its peak would produce 50-mile-an-hour winds, and waves that crested at 50 feet – about as tall as the ship from waterline to the top of the smokestack. Our dad, Signalman George K. Broatch, was one of 204 Royal Canadian Navy crew members and officers aboard the ship.

Skeena finally dropped anchor around 10:30 that night between Engey and Videy Islands, and most of the crew was ordered below decks to get some sleep. But around midnight the Skeena received an urgent message from a nearby sister ship, the St. Laurent, that Skeena was drifting away from her anchorage point. The ocean floor in the area was apparently known to be “soft” and difficult to anchor in. Speculation later was that the drift was not obvious to crew members on Skeena’s deck because of darkness, snow flurries, and the surf’s constant pounding against the ship.

In spite of the crew’s frantic last-minute efforts to set another anchor, the wind and waves drove Skeena onto the volcanic rocks off Videy Island. The life boats on the seaward side of the ship were destroyed by wind and waves. When the jagged rocks punched several large holes in the bough of the ship, the seawater began pouring in.

Although Skeena was only 100 yards from shore, the rough sea and rocks didn’t allow the crew to use life rafts or other inflatables to escape the ship. Also, the water was freezing cold and covered with oil from the ship’s engines. Tragically, fifteen sailors who responded to an early command to man the lifeboats – a command that was almost immediately revoked – died soon after of drowning or exposure. Some apparently lost their flotation devices and washed into shore on Videy Island. Survivors among those sailors were reportedly taken to nearby fishermen’s homes to be warmed up and cared for. Amazingly, the powerful southwest winds carried others on their flotation devices more than five miles northeast across the sound from Videy Island to Mogilsa, on the mainland. Survivors in this group were taken to a farmhouse for care.

On the ship, meanwhile, water-tight hatches and doors below decks had been locked against the incoming seawater. But, Skeena was still in danger of sinking in the 75-foot-deep water, and even of breaking up. Fortunately for the ship’s remaining crew, a brave and skilled Icelandic fishing boat captain named Einer Sigurdsson was soon to arrive to supervise their rescue. In the morning light of October 25th, in continued stormy weather, he piloted what was described as a “small landing craft” to the leeward side of Videy Island. The seas were still too rough to navigate on the windward side. Then, on foot, he and others lugged the rescue equipment across the island to the ship.

Although I did not find a detailed description of the rescue, there was mention in one account of “a line” being set up. And a survivor described being transferred from the ship to shore in a “bosun’s chair”. A quick internet search revealed that, from the late 1920’s, mariners and others used specialized line-throwing guns and cannons that could fire a rescue line from water (or ground) level onto a ship deck. Also in use were light but strong seats, or bosun’s chairs, with clips that attached to the rescue line. So, Skeena’s sailors – cold, hungry, and exhausted, with several injured – were likely maneuvered slowly, one by one, down the line to safe, solid ground.

The line was secured at the ship and shore ends, and used a block-and-tackle kind of set up, based on the same general idea as safety lines used by mountain climbers or skyscraper window washers. Einer Sigurdsson stood in water up to his waist, likely for several hours, supervising the operation. His daughter remembers that he came home coated with engine oil.

I assume survivors were housed in barracks located in Iceland and administered by the United States military. A historical note may be useful here. Great Britain technically occupied Iceland beginning in 1940 – much to the neutral Icelanders’ outrage. Winston Churchill feared that Hitler would invade and occupy the tiny island nation, and he didn’t want Nazi armed forces based that close to home. In 1940, Canadians were recruited to administer the occupation, and in 1941 the Americans got the job. (Source: Itinerant Historian blog.)

On October 28th, fourteen men who died in the shipwreck were buried, with full naval honors, in the Fossvogur Cemetery in Reykjavik. The 15th man was eventually listed as missing and presumed drowned. Five hundred U.S., Canadian, and British military personnel, as well as local people, attended. A memorial stands today on Videy Island to honor Skeena’s dead and to pay tribute to rescue leader, Einer Sigurdsson.

Skeena sailors may not have anticipated what happened next. According to a memoir penned by Bill Braun, who was the Upper Deck Stoker when Skeena was wrecked, he was taken to a U.S. hospital for care, and later to Glasgow, Scotland. He reported then being transported on the Queen Elizabeth II from Glasgow to New York and then Montreal.

According to Mr. Braun, he received 180 days of survivor’s leave, plus 60 days of accumulated leave. (Source: For Posterity’s Sake, a privately run website dedicated to preserving Royal Canadian Navy history. His son, Bill Braun, submitted his father’s memoirs to the website.) Assuming this was the protocol for all the survivors, Dad’s combined leave would have ended in late June of 1945, about six weeks after his marriage to our mom, Catherine E. Johnston. I don’t know whether Dad had to return to RCN duty afterward.

Oddly, the RCN press releases about the event were not sent out until seven months later, on May 16, 1945, possibly because of unresolved questions about what happened and who bore what responsibility for the shipwreck. Or maybe they were simply asked to hold the press release until after the war in Europe ended.

Sources for information about the shipwreck include the Cowichan Valley Citizen newspaper, Cowichan, B.C., Canada, November 8, 2017 issue; the For Posterity’s Sake website, a private site for conserving Royal Canadian Navy history, not associated with the government of Canada or the Department of Defense; the Itinerant Historian website; and the militarywikia.org. All accessed between November 2 and 4, 2021.

12 responses to “”

Well done!

Thanks! It was really interesting to research. The only anecdote Dad told me about the wreck was that, when the sailors were brought ashore in Iceland, and the captain was recruiting volunteers for camp duty, he and Curly McDowell decided to volunteer for KP right away, “because all the other jobs would be much worse.” I’m not sure what that meant, exactly.

This is so interesting! Thanks a ton!

Thanks. Did your dad share any of his navy history with you?

My god! We’re all lucky to even be here. A harrowing story. KP sounds good and warm after that.

Keep them coming, so good to know our family history.

Mary

That’s exactly what I thought as I was writing this. Your dad was in even more dire straits in Burma. I hope Patrick cranks out a story about that.

Thanks for your comment.

Congrats on another wonderful story! You are a treasure for us and our children and their children for many years to come.!

Thank You a million Linda for all your stories. I look forward to them. Our local OGS in Chatham is interested in military info, especially at this time of year when we remember and acknowledge the bravery of our men & women of Canada. There is a person who is supposed to be writing a book about the skirmishes along the St Clair River in the 1830s between Canada and some USA men. That is where my great-great-grandfather contracted pneumonia and died in Dec 1840. I hope to get a copy of their book. Please keep up the posts as many of us have no idea of the details of the lives of our families. Harold

You’re more than welcome, Harold. You have given me so much help with the Snary family line in recent years that I’m glad I can provide some family history of interest to you. Linda

Thanks so much Linda. I love these stories, and the history lesson that comes with them!

Wishing to get in touch with Linda the author of the Skeena Story. I have been researching the loss of Skeena for many years and have taken survivors to Iceland multiple times to see the Skeena propeller monument. I have collected many artifacts from the ship and they are on display in Port Hope, Ont. In my possession I have the ship’s bell including a hospital gown that was signed by all the sailors who were in the US hospital after being rescued. Please contact me.

Hi, Chris — Thanks so much for contacting me about the Skeena story. When I was searching online for information about HMCS Skeena, I saw articles about the current day cadet groups working on the ship’s history.

What a great project to work on! My hope, Covid outbreaks permitting, is to visit some of the places in Canada related to my family’s history. I’m not getting any younger, so I hope that opportunity comes soon.

For now, I’ll keep searching away on my computer, at home in Washington State in the U.S. Very nice to hear from you, and keep up the good work.

Kind regards,

Linda